The Philosophy Café

This month's topic: Property Rights and The Commons

DateApr

17

Wednesday

April 17, 2013 7:30 PM ET |

LocationUsed Books Department

1256 Massachusetts Ave., Cambridge, MA 02138 |

Tickets

This event is free; no tickets are required.

|

The Philosophy Café at Harvard Book Store is a monthly gathering meant for the informal, relaxed, philosophical discussion of topics of mutual interest to participants. No particular expertise is required to participate, only a desire to explore philosophy and its real-world applications. More information can be found at www.philocafe.org.

The Philosophy Café is held on the third Wednesday of each month at 7:30 in the Used Book department on the lower level of Harvard Book Store.

This month's topic: Property Rights and The Commons

Philosophy, religion, and economics all attempt to address the tension that exists between what is seen as the right to privately held property and the material inequities that exist between individuals and social groups. Recent political debates expose the temptation of those at the top of the economic ladder to blame the plight of the poor on factors rooted in the behavior of the poor themselves. The April discussion will focus on attempting to define an ethical standard that helps us in our quest to create an economic system that recognizes the right to private ownership at the same time it facilitates the equitable and sustainable distribution of wealth.

In The Second Treatise of Government (1689), John Locke starts with a description of humans in a state of nature and bound only by natural law. Under such a system, any human has an ethical right to privately hold that which his or her—I’ve updated Locke’s use of personal pronouns—own labor produces. He states, “And indeed it was a foolish thing, as well as dishonest to hoard up more than he could make use of.” Locke understands that wealth is created when such labor is applied to “…a property…that God gave to mankind in common.” Modern theorists sometimes refer to this as “the commons in nature.” Locke notes that productive increases in the commons derive from human activity applied to those natural resources. In Locke’s time, this was most fully evident in labor that enhanced the productivity of land. From that observation, he seems to conclude that since humans have made this increase possible, they have claim, not only to the bounty that results from their labor, but also to the plot of land itself.

Locke later acknowledges that human greed and the invention of money distort the amount of land any individual might claim. Since he has earlier labeled hoarding “dishonest”, we’ll discuss whether his faith in the ability of the positive constitutions of government to legislate “the rights of property and possession of land” has been up to the task of preventing greed from distorting human economic systems.

Today, the problems that Locke saw in allowing monopoly holdings in land are also inherent in a wide range of other naturally occurring resources: clear water, clean air, mineral reserves, the electro-magnetic spectrum, biological genomes, etc..Is there an inherent logic in applying different ethical and legal assessments to different types of property? How can we prevent the guarantees afforded intellectual property rights from becoming monopolistic barriers to invention?

Henry George began with the ethical premise that all people have an equal right to the use of the earth. From that he concluded that exclusive private ownership of land (natural resources) creates unwarranted special privileges. Furthermore, he observed that holding land out of production drives down real wages and the returns to capital equipment. This process is further exacerbated by taxes on production and income that:

increase unemployment

discourage productive investment

encourage unproductive land speculation and rent-seeking

To counteract this self-destructive system, George advocated shifting taxes from labor and capital onto the value of land and natural resources.

The discussion of these issues is made more difficult by the failure to clearly define the terms. For many people rent is something the landlord collects from his tenants. However, the criticism of rent-seeking that is applied to today’s economic behavior is a complaint against the private appropriation of the excess in value that comes, not from the effort of the individual owner/owners, but from the special privilege afforded to monopoly holdings that block access to something that more properly might be seen as an element of the commons in nature. In Progress and Poverty (1879), Henry George offers this definition of economic rent. “The rent of land is determined by the excess of its produce over that which the same application can secure from the least productive land in use.” Land is usually considered as just another element of capital. However, conflating capital with land (i.e. natural resources) leads to inherent contradictions. The flawed logic inherent in combining the two is exposed by considering the different ways classic categories of capital and land respond to the laws of supply and demand.

The ever-increasing gap between rich and poor is generally seen as a threat to national and international well-being. Debate over appropriate sources of public funding has locked the legislative bodies of the U.S. government into a dysfunctional gridlock. Climate change and the exploitative destruction of the environment produce legitimate concerns about the fate of all species. Suddenly, there is a recognition of the need to curb rent-seeking behavior and to charge the proper parties for the costly “externalities” of war and production that too often are passed onto an unsuspecting public. Is there a way to stop this privatization of profits and socialization of costs? Thomas Friedman’s Op-Ed piece, referenced below, offers a glimpse into a way out of the abyss.

Challenges may come from those who consider freedom and self-determination to be threatened by regulation of our common and shared land resources. We hope to illuminate dynamics in our economic system that will lead to a fuller understanding of how money, labor and real property are distributed and accounted for.

Readings

Chapter Five, “Of property”, from The Second Treatise of Government by John Locke. http://www.constitution.org/jl/2ndtr05.txt

Progress and Poverty by Henry George http://schalkenbach.org/library/henry-george/p+p/ppcont.html

“With so much wealth in the world, why is there still so much poverty?” from “The Narrative Framework” of the film The End of Poverty? http://www.theendofpoverty.com/narrative_framework_1.html

“It’s lose-Lose vs. Win-Win-Win-Win-Win” by Thomas L. Friedman : http://nyti.ms/ZISQwM

Rent-seeking , definition Wikipedia : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rent-seeking

Urban Land as Common Land, from Guernica Magazine: http://www.guernicamag.com/daily/rich-nymoen-jeff-smith-reviving-the-idea-that-urban-land-is-common-wealth/

Walking from the Harvard Square T station: 2 minutes

As you exit the station, reverse your direction and walk east along Mass. Ave. in front of the Cambridge Savings Bank. Cross Dunster St. and proceed along Mass. Ave for three more blocks. You will pass Au Bon Pain, JP Licks, and the Adidas Store. Harvard Book Store is located at the corner of Mass. Ave. and Plympton St.

(617) 661-1515

info@harvard.com

Media Inquiries

mediainquiries@harvard.com

Accessibility Inquiries

access@harvard.com

Classic Totes

Tote bags and pouches

in a variety of styles,

sizes, and designs, plus mugs, bookmarks, and more!

Shipping & Pickup

We ship anywhere in the U.S. and orders of $75+ ship free via media mail!

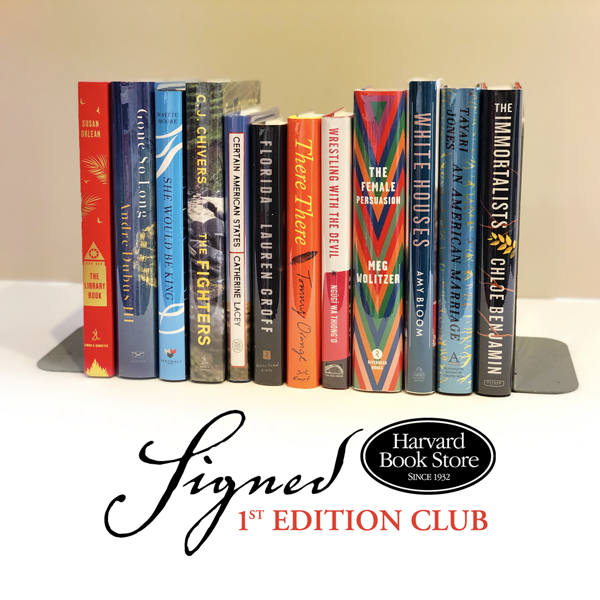

Learn More »Noteworthy Signed Books: Join the Club!

Join our Signed First Edition Club (or give a gift subscription) for a signed book of great literary merit, delivered to you monthly.

Learn More »